November 22, 2014

Photo by Nancy Cutway

Photo by Nancy Cutway

Jean Rae Baxter spoke on “The Education of a Leader: Joseph Brant and the School that became Dartmouth College”. Jean is a former English teacher at Napanee District High School. Now retired to Hamilton, she has written a number of historical novels for young adults, all dealing with Loyalist themes. As she said, by the time she published her third book, her publisher said “Now we have a trilogy.” Her fourth novel was published this year and her fifth is well under way, so now the publisher is calling it the “Forging Canada” series … leaving the number open-ended!

Joseph Brant was born in 1743 in Ohio Territory. His father was a Mohawk named Tehowah-wengaragh-kwin, which means “A man taking off his snowshoes.” Joseph’s Mohawk name was Thayendanegea. His father and mother (known to us only as Margaret, likely a name bestowed on her when she became a Christian) also had two children who died young before their daughter Molly was born in 1736. Tehowah-wengaragh-kwin died, and Molly and Joseph’s mother Margaret married a man named Brant Canagaraduncka, an important sachem among the Mohawks. They adopted his name “Brant” as their surname. Their new stepfather was a man of importance: archaeological digs have shown that his house in Canajoharie, New York Province had a stone cellar, clapboard siding, glass windows, and stone fireplaces. Brant Canagaraduncka’s home was a frequent stopping place for Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs. Sir William acquired much land and wealth, and was the largest slave owner in the north (15). As most readers will know, he entered a relationship with Joseph’s sister Molly, who bore him eight children.

Sir William also took an interest in Joseph Brant and when he was 18, in 1761, he was one of 3 boys recommended that year by Sir William to Rev. Eleazar Wheelock, a Congregational minister who set up the Moor Indian Charity School in Lebanon CT. The prep school was established by the Scottish Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge in the Highlands and Islands and Foreign Parts of the World. Its purpose was to teach basic reading and writing to natives of both genders: in 1761 when Joseph attended school there were 15 boys and 7 girls representing 10 differnt tribes. It was also intended to provide the training they might need to become missionaries to their own people. Jean Rae Baxter’s latest novel, The White Oneida, contains a fictitious account of life at such a school, based in part on the Moor School records which survive.

The Moor School was so successful that by 1769, Wheelock recognized the need to establish a college at a more advanced level, and created Dartmouth College. Its motto still is Vox Clamantis in Deserto, “a voice crying in the wilderness”. The college was named for the Earl of Dartmouth, the largest donor when another native student, Samson Occom (the first student Wheelock tutored before founding his school) completed two years of fundraising up and down the United Kingdom. Samson had astonished Rev. Wheelock by learning Latin, Greek and Hebrew in addition to English.

Sir William Johnson withdrew Joseph from the school after two years, wanting him to attend King’s College in New York City, but the 1764 Pontiac Rebellion intervened. Instead, Sir William entrusted his education to a tutor, Cornelius Bennett, who unfortunately left very soon to avoid a smallpox epidemic in 1765. After that, Joseph Brant was hired as an interpreter for the British. He married an Oneida girl named Peggy and they farmed near Canajoharie.

In 1770 Joseph met Rev. John Stuart, and when Peggy died in 1771, Stuart invited Joseph to live with his family in the Fort Hunter parsonage. Together they translated the Anglican Prayer Book and the Gospel of Mark into the Mohawk language.

Education was always important to Joseph Brant. He sent his own sons to Moor School, and the first teacher at the school in Brantford, Upper Canada established after the Mohawks settled on the Six Nations Reserve was Paulus, a graduate of Moor School. A later schoolmaster at the Brantford school was George Johnson, a son of Sir William Johnson and Molly Brant.

Joseph’s third son, John, was elected to the Upper Canada Assembly in 1830 and was the first native member of an elected assembly in Canada. However, his election was challenged because he was not a property owner — since the Six Nations owned their land grant along the Grand River communally. His opponent John Warren was declared elected in 1831. John protested, but the issue became moot when both John Brant and his challenger died of cholera during the 1832 epidemic.

Joseph got in trouble with the Mohawks for disregarding the policy of communal ownership and selling off some land to a Mennonite group who settled in Waterloo County; he probably felt that the new settlement needed some ready cash and this was a way to benefit the community, but others did not see it that way. Joseph spent the last 12 years of his life in Burlington rather than Brantford, avoiding conflict with the rest of the tribe. He died in 1807.

September 27, 2014

Loyalist Tales was the topic for the meeting, and several members told interesting stories.

Loyalist Tales was the topic for the meeting, and several members told interesting stories.

First up was Sue Kilpatrick. Her Loyalist ancestor was Reuben Scott who, with his wife Sarah Keeler, settled in Colborne, Ontario. Their son Reuben Bartlett Scott built an octagonal house about 1850. It was the only one in town, and probably the only such architecture for many miles around. Sue showed a photo of the house as it originally appeared, and a more recent photo showing stucco now covering the brick. The house still is a family home, at 45 Parliament Street in Colborne.

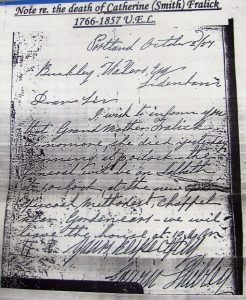

Lyn Bell showed some documents connected to two of his Loyalist ancestors. On the death of Catherine Smith Fralick UE in 1857, her grandson Garnet Shibley sent a note from the village of Portland to a gentleman in the village of Sydenham, informing him of her passing and the time and date of her funeral. Lyn reflected on the contrast to our day, when it’s easy to place a death notice in a newspaper and on websites.

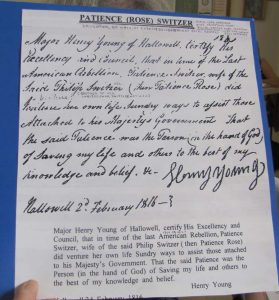

The other document was a testimonial written by Major Henry Young of Hallowell about Patience Rose Switzer, who may have been eastern Ontario’s counterpart to Laura Secord. Lyn is not certain if “the last American Rebellion” refers to the War of 1812, since the document was written in 1816.

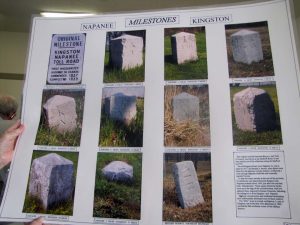

Lyn also showed a collection of the remaining milestones between Kingston and Napanee. Originally there were 23 of them along the Kingston Road [now Highway 2]. They were set at a 45 degree angle to the roadway so that one face gave the distance to Kingston, and the other showed how far remained to reach Napanee. Depending on which direction you were heading, you looked for N or K and a number. The stone reading MR, in the lower right position, was erected in 1829 to mark the northeast corner of the Military Reserve east of Kingston (now on CFB Kingston).

Jim Long talked about the Schneider Enfield rifle his father Ross owns. (Ross was intending to speak himself, but didn’t get to today’s meeting.) The rifles were issued about 1865, but were sold off for $2 when the British Army left Canada, and a Long ancestor bought one. Jim had a photo of his dad and a friend cleaning and firing the gun. Watch for the photos and article to appear in a future newsletter. By the way, it’s the same gun that is still used by the Fort Henry Guard during their demonstrations, but theirs of course are loaded with blanks.

Audrey Bailey spoke about Henry Merkley UE. His father Christopher had come from Wurttemburg, Germany to Tryon County, New York. Henry was born in Scoharie, NY. His name appeared in the minutes of the New York Commissioners for Conspiracies even before the Revolution, and he spent three years in the Scoharie jail. He was released, but on 20 May 1777 he was fined £5 and made to give his oath of allegiance to America … but he joined the King’s Royal Rangers of New York 3 months later!!

Sir John Johnson referred to him in a letter as being “… of a very fair and honest character.”Henry was a lieutenant in the Dundas Militia by 1803, and in 1813 he was at the Battle of Crysler’s Farm as a Major. He was a Member of Parliament in the 4th parliament of Upper Canada. His tombstone is in the wall of the Loyalist Memorial Cemetery at Upper Canada Village.

Sir John Johnson referred to him in a letter as being “… of a very fair and honest character.”Henry was a lieutenant in the Dundas Militia by 1803, and in 1813 he was at the Battle of Crysler’s Farm as a Major. He was a Member of Parliament in the 4th parliament of Upper Canada. His tombstone is in the wall of the Loyalist Memorial Cemetery at Upper Canada Village.

Audrey has no image of Henry Merkley UE, but showed us photos of his son Henry Jr., and of her great-grandfather Merkley.

May 27, 2014

As part of our celebrations of the 100th Anniversary of the United Empire Loyalist Association of Canada, we gathered on Tuesday, May 27th for a luncheon at the Donald Gordon Centre. We were serenaded beforehand by Danielle Lennon, a charming violinist. Danielle also played for the singing of “God Save The Queen” after the Loyalist Colours were brought in by Jim Long.

As part of our celebrations of the 100th Anniversary of the United Empire Loyalist Association of Canada, we gathered on Tuesday, May 27th for a luncheon at the Donald Gordon Centre. We were serenaded beforehand by Danielle Lennon, a charming violinist. Danielle also played for the singing of “God Save The Queen” after the Loyalist Colours were brought in by Jim Long.

Mayor Mark Gerretsen was unable to stay for lunch, but graciously spent some time speaking with most present, and then brought official greetings on behalf of the City of Kingston.

We enjoyed a great meal, and lots of interesting conversations.

We enjoyed a great meal, and lots of interesting conversations.

Speaker Paul Banfield (right, rear table) listens earnestly to local Loyalists.

Our guest speaker was Paul Banfield, Queen’s University Archivist. Paul delivered a very interesting talk about the Archives — both the practicalities of location, parking and hours, and its mission to serve Queen’s University and the community. He gave some interesting facts:

- The first document collected by the university for its Archives is a Quartermaster’s Paybook from Niagara during the War of 1812 — acquired in 1869.

- The archives is currently housed in Kathleen Ryan Hall, a building formerly known as the “New Medical Building”. During the Second World War, the top two floors were loaned to the Department of National Defence, which performed top-secret experiments on potential germ warfare. Fortunately those germs are long gone!

- The Archives holds 11 kilometres of boxed records, over 2 million images from the 1850s onward, around 100,000 architectural plans and drawings, and 15,000 audiovisual records.

- The Archives houses Queen’s 1841 Royal Charter from Queen Victoria establishing the university on October 16, 1841. Surprisingly, it was not signed by the Queen, but by a bureaucrat named Leonard Edmunds.

For people researching United Empire Loyalists, there is much information available. The papers of Dr. H.C. Burleigh, who collected information on over 1,000 families who settled in the Kingston area, are now digitized and available online. The Archives also hold papers of Rev. Wm. Bell and Rev. Robert McDowall, early clergymen in this area; the Cartwright family, the Fairfield family, the Jones family 1787-1940s, the Parrot family, and the papers of Benjamin Seymour 1796-98. On microfilm they have the papers of Sir Frederick Haldimand and the Loyalist Studies Project. They also hold Tweedsmuir Histories compiled by members of area Womens’ Institutes.

For people researching United Empire Loyalists, there is much information available. The papers of Dr. H.C. Burleigh, who collected information on over 1,000 families who settled in the Kingston area, are now digitized and available online. The Archives also hold papers of Rev. Wm. Bell and Rev. Robert McDowall, early clergymen in this area; the Cartwright family, the Fairfield family, the Jones family 1787-1940s, the Parrot family, and the papers of Benjamin Seymour 1796-98. On microfilm they have the papers of Sir Frederick Haldimand and the Loyalist Studies Project. They also hold Tweedsmuir Histories compiled by members of area Womens’ Institutes.

Paul concluded with a slide show of recently-acquired photos taken about 1894 by photographer James W. Powell. We all enjoyed the views of buildings as they were 120 years ago.

May 29, 2014

After our sandwich ‘n square lunch, and our brief business meeting, president Peter Milliken provided a most interesting tribute to his late cousin John Matheson, UE. Other sources refer to our late member as “John Ross Matheson, OC CD QC (November 14, 1917 – December 27, 2013)” and state that he “was a Canadian lawyer, judge, and politician who helped develop both the maple leaf flag and the Order of Canada” [Wikipedia] but fail to note that John was a very proud descendant of Charles Rose, UEL. Peter informed us that he didn’t have to do any work towards obtaining his own UE certification: his mother’s first cousin, John Matheson, just filled out the form and told a young Peter to sign! Of course, John was for a time the Honorary President of UELAC, and a long-time member (including being president) of Sir Guy Carleton Branch when he lived in Ottawa. He enlisted as many family members as possible to become members and swell the ranks of the organization.

After our sandwich ‘n square lunch, and our brief business meeting, president Peter Milliken provided a most interesting tribute to his late cousin John Matheson, UE. Other sources refer to our late member as “John Ross Matheson, OC CD QC (November 14, 1917 – December 27, 2013)” and state that he “was a Canadian lawyer, judge, and politician who helped develop both the maple leaf flag and the Order of Canada” [Wikipedia] but fail to note that John was a very proud descendant of Charles Rose, UEL. Peter informed us that he didn’t have to do any work towards obtaining his own UE certification: his mother’s first cousin, John Matheson, just filled out the form and told a young Peter to sign! Of course, John was for a time the Honorary President of UELAC, and a long-time member (including being president) of Sir Guy Carleton Branch when he lived in Ottawa. He enlisted as many family members as possible to become members and swell the ranks of the organization.

John graduated from Queen’s University in 1940 and immediately enlisted in the Canadian Army. He was severely wounded at Ortona, Italy and left on the battlefield. Peter related that a chaplain, Waldo Smith, told him many years later that he personally went onto the field after battle had ceased, found John, and carried him back to the camp to be hospitalized. John was repatriated to a hospital in Canada, where his future wife Edith was a nurse. Their six children are Peter Milliken’s second cousins.

After the war, John Matheson returned to university and became a lawyer, settling in Brockville, Ontario. He first won a by-election in Leeds & Grenville in 1961. He was then returned as MP in the elections of 1962, 1963 and 1965. He served as Parliamentary Secretary to Prime Minister Lester Pearson. Peter was always interested in Parliament from a young age, and was delighted to visit his mother’s cousin in Ottawa: John would take him to sessions of the House, and would introduce him to such figures as Pearson, John Diefenbaker, and Pierre Trudeau (who was the other Parliamentary Secretary to the PM along with John).

John lost the 1968 election by just four votes. After leaving politics, he was appointed as a judge and served in that capacity for a number of years.

Peter told us that John’s personal legacy includes 18 grandchildren and one great-grand-child. But his legacy to the country is much larger: during the seven years he was in the House of Commons, he was the co-founder of the Order of Canada, and the co-designer of the Canadian Maple Leaf flag. He was adept at achieving compromise, says Peter, and that’s why his committee work was so successful.

We were pleased to hear these personal insights into a man who many of us knew only in his later years after he retired to Kingston and occasionally attended our local meetings. He accomplished much good for Canada, and leaves an example which today’s politicians would do well to emulate.

January 25, 2014

Our speaker was to have been Peter Milliken. When Peter was unexpectedly not available, John Fielding graciously stepped into the breach and spoke to us about British Home Children.

Our speaker was to have been Peter Milliken. When Peter was unexpectedly not available, John Fielding graciously stepped into the breach and spoke to us about British Home Children.

While a hundred years or more separated the arrival of United Empire Loyalists to what would become Canada, and the gradual arrival of Home Children between about 1870 and the Second World War, there were some similarities between these two groups of refugees. All of them were leaving their previous life and starting over with nothing. Most had a very difficult life — but most worked hard and left their descendants with the legacy of a brighter future. All should be honoured for their perseverance.

When John began his research, he thought his father, sent to Canada as a boy, had been an only child. It turned out there were older siblings in England, and John has met their descendants. You never know where family research will take you!