Adapted from The Loyalist

Gazette Vol. XXIX, No. 2 Fall 1991

By Gerald A. Rogers, Heritage Branch

With Editorial Footnotes by Michael Rice, 2004

Over the years many articles and books have been written on the Iroquois

Confederacy or the Six Nations Indians, particularly during the period

of and following the American Revolutionary War. Much of this information

has had to do with the Mohawks of New York State and the Province of Ontario.

It includes their settlement along the Grand River and the Bay of Quinte

under their chiefs Joseph Brant, John Deserontyon and others. Very little

has been written, except by French authors, on the Mohawks or the ‘Christian

Indians’, who were settled by the Government of New France, with

the spiritual guidance and protection of Catholic religious orders, at

several locations in what is now the Province of Quebec.

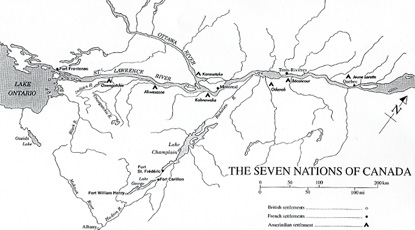

These included Mohawks or members of the Iroquois Confederacy at Caughnawaga

(now Kahnawake), at Oka (now Kanesatake) and at St. Regis (now Akwesasne)

as well as Hurons settled at Lorette and Abenakis at Becancour and St.

Francis.

|

|

During this past year and the summer of discontent, the troubles at Oka and at Kahnawake, with the closing of the Mercier bridge, brought the natives of these communities more publicity and exposure than every before. It became not only a national but also an international issue and aroused thousands of Canadians to participate in thought, opinion and even direct action. It dramatically affected the daily lives of hundreds of Quebec residents. The media had a field day. There was a great deal of misinformation, twisting of facts and exaggeration on both sides. Unfortunately also, the majority of Canadians from the other provinces, knowing little of nothing of Mohawk history in Quebec, were at the mercy of the media, which did little to enlighten them.

The Mohawks of the Six Nations Confederacy or the League of the Iroquois, which also included the Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, Senecas and Tuscarores had moved by the turn of the seventeenth century, from the valley of the St. Lawrence to villages along the Mohawk River, west of Albany. They had also become bitter enemies of New France. In July of 1609, Samuel de Champlain, during his first exploration of the lake that was to bear his name, met a band of Mohawks. In a skirmish that took place, many Indians were killed and thus began a French/Iroquois conflict that lasted a hundred years and more.

By 1650, the Mohawks had destroyed the Huron missions on Georgian Bay, the Neutral nation along Lake Erie and had even raided as far as the upper Ottawa and the St. Maurice Rivers, threatening Three Rivers and even Quebec City. Their constant raiding terrorized the settlers along the St. Lawrence and even discouraged colonization. De Tracy with the Carignan-Sallières regiment was sent out from France to crush the Iroquois. In 1666, the army penetrated the Mohawk country, burned their villages and destroyed the winter food stocks. The Mohawks sued for a peace that lasted nearly twenty years. One of the many benefits was the opportunity to renew missionary efforts among the Indians.

The Jesuits or the ‘Black Robes’ as the Indians called them had first travelled to the Mohawk valley in 1642, there to begin the conversion of the Indians to the Catholic faith. Over the years many were martyred for their efforts and included Father Isaac Jogues, Rene Goupil and Jean de la Lande. They were killed at Ossernenon (Auriesville), where Kateri Tekatwitha, the ‘Lily of the Mohawks’ had been born in 1656. It was here in 1667, among the ashes of a once prosperous village, that the Jesuits renewed their Christian mission. They found among the Mohawks many captives, mainly Hurons, who had maintained their faith and now helped the missionaries not only with conversions but also in persuading several to follow the Jesuits to their seigneury at Laprairie. Here at the mission of St. Francis Xavier, they received instruction in the Christian religion and were encouraged to follow their agricultural way of life.

Father Jacques Fremin, the superior at Laprairie, was always hard pressed in preventing French traders from plying their liquor trade among the Indian. By 1676, he was faced with other and more important problems. The cropland was wearing out. They had to travel longer distances for firewood and there was serious over-crowding at the mission. The Indian families at Laprairie had become more numerous than in their own country. In this same year, the mission moved to the Portage River, near the foot of the Lachine Rapids where in 1670 a church was erected. Kateri Tekakwitha died here in 1680. At the time of the move, Father Fremin arranged with the Sulpicians to take some of his Mohawk, Huron and Algonquin Indians, to their Mountain Mission at the foot of Mount Royal on the Island of Montreal.

In 1690, the village moved closer to the rapids at Kahnawakon, where the first water-powered gristmill was erected. This old mill stood until just a few years ago and even today a few stones remain in the millrace. It was in August of this same year that the massacre at Lachine took place. Historical writers vary widely on the number of settlers killed or taken prisoner and even on the reasons for the attack. Some say over two hundred but more recent studies indicate not more than fifteen or twenty. Even today many people blame the Indians at Caughnawaga. The real reason can be laid at the doorstep of the Marquis de Denonville, then Governor of New France. He had devastated the lands of the Iroquois and in 1687 arranged a meeting at Cataraqui (Kingston) of Iroquois chiefs to discuss peace plans. Instead, he seized forty of them who were sent to France as galley slaves. They gained their revenge at Lachine.

In 1696, the mission moved above the rapids to the mouth of the Suzanne River and the village was built on a slight elevation overlooking Devil’s Island. While here at Kanatakwenke in 1704, plans were laid for the Deerfield raid and bringing back the famous Deerfield bell. Over three hundred French and Indians, including some Abenakis were assembled under the leadership of Hertel de Rouville. They attacked the village in the early morning hours of February 4th and returned with many white captives including Eunice Williams, the daughter of the Rev. John Williams. The taking of New England captives was a common practice during the French regime and was encouraged by Government and Church. The Mohawks and the Abenakis were the main participants and many white children and even adults were adopted by Indian families or ransomed. Indian families proudly bear the names of Gill, Williams, Rice, Tarbell, Hill, Stacey, Jacobs, McGregor, etc. The bell was brought back and installed in the church belfry. Truth or myth. Many stories have been told of this famous bell. Did it exist or was the raid planned by the French to take Deerfield and the story of the bell used as a rouse? It is a well documented fact that the French raided and scalped with the Indians.

The fourth and final move to present day Kahnawake or Caughnawaga was made in 1716. By 1720, the present stone residence of the Jesuit missionaries had been erected and by 1725 Fort St. Louis established with stone walls around the church and residence area. Old pictures indicated a wooden palisade around the rest of the village, no doubt as protection against Indian raids from the Mohawk Valley. By 1750, other stone residences had been built as officer and troop quarters. There has always been a very strong French presence in the village, from the days of Chevalier de Lorimier. Many of the stone buildings as well as part of the fort walls remain to this day. The rectory building is connected to the church, built in 1865, through an interesting old museum. Many ancient relics have been preserved here including Iroquois/French dictionaries, a grammar of the complicated Mohawk language, many manuscripts and parish records as well as baptismal records from 1735, a chalice from Empress Eugenie, a ciborium, a silver monstrance presented to the Jesuit fathers in 16568 and a wampum belt given by the Hurons to the Mohawks in 1676. There are also the famous bells, the one supposedly from Deerfield and another presented in 1832 by William IV of England.

About fifteen years after the Deerfield massacre, two young brothers of the Tarbell family were captured in Groton, Massachusetts, taken to Caughnawaga and adopted into native families. They grew up in the manner and habits of the Indians and married Chief’s daughters. However, their differences caused a great deal of trouble and eventually with their own, as well as several other families, they left the village. They coasted along the south shore of Lake St. Francis and settled on a beautiful elevated point between the St. Regis and Raquette rivers. In 1755, they were joined by Father Antoine Gordan ( Gordon), a Jesuit from their old village. He established the first mission and named the place St. Regis, after Jean Francois Regis of the Society of Jesus.

Father Gordan also built the first log church which was lost by fire, together with the parish records. The present stone church was erected about 1792 under the direction of Father Roderick McDonnell, a Scottish priest from Glengarry. He had arrived in 1785 and remained until his death in 1806. He was fluent in not only the Gaelic but also English, French and the Mohawk dialect. Succeeding priests included: Fathers Rinfret, Jean Baptiste Roupe, Joseph Marcoux, Nicholas Dufresne, Joseph Valle and the Rev. Francis Marcoux. Father Joseph Marcoux spent six years at St. Regis before leaving for Caughnawaga. There he undertook the financing of and building the present stone church, completed in 1845.

During the American Revolutionary War, many of the St. Regis Indians joined the British cause, while others under the influence of Louis Cook, supported the Americans. Unfortunately there is very little reliable information that has been published for this time period and the Indian participation. We do know that Father Gordan died in 1777 and only two years before his death, marched as Chaplain with Mohawk warriors, to Fort St. John on the Richelieu. There are many records extant from 1795 on, of several treaties entered into by the Mohawks of St. Regis and Caughnawaga with the State of New York and pertaining to land disputes in the Northern part of the State. When the international border was struck, the line passed through and divided the village and lands of St. Regis, with the larger part in New York State. A census of 1852 shows 630 Canadian and 490 American Indians residing at St. Regis, now officially known as Akwesasne.

Several of the chiefs and head men at St. Regis were of part white extraction, many descending from New England families. Up until 1820, the names of Louis Cook, William Gray, Captain Thomas Williams and Loren, Lesor and Peter Tarbell, appear on treaty papers. They were then followed by sons and nephews: William L. Gray, Charles Williams, Michael, Loren and Charles Cook and Thomas and Joseph Tarbell. Thomas Williams was originally a Caughnawaga chief and Peter “ The Big Speak” Tarbell, was a son of Lesor Tarbell, one of the brothers captured at Groton.

The life story of Louis Cook is of particular interest as he enjoyed great influence at both villages of Caughnawaga and St. Regis. He was born about 1740 at Saratoga, N.Y., of a black father and an Abenaki Indian mother. In appearance he strongly resembled his father. During a raid on Saratoga in 1755, he and his family were captured and taken to Caughnawaga. There the Jesuits persuaded Louis to live with them as an attendant and to learn the French language.

During the Seven Years War, Louis took arms with the French and in 1756 was wounded in a skirmish with Roger’s Rangers near Ticonderoga. He was with the French troops on the Ohio, at the taking of Oswego, at Ticonderoga and in the attempt to retake Quebec. At the beginning of the Revolutionary War in 1775, we find him visiting George Washington, to report on the temper and disposition of the Quebec Indians. At that time he reported that five hundred Caughnawaga Indians were able to bear arms, but that they and the French preferred to remain neutral and at peace. However, at a later date, he and a handful of Canadian Indians joined the American cause.

He received a commission on raising a company of Oneida warriors to fight with him. Following the declaration of war in 1812 and though born down by the weight of more than seventy years, he joined the Americans. He was at Sacketts Harbour in 1814. Later that year with his sons and several St. Regis warriors, he was actively engaged on the Niagara frontier. There he was directly opposite and opposed to other St. Regis and Caughnawga Indians under de Lorimier and Ducharme at Beaver Dams. The latter distinguished themselves and almost single handedly captured a detachment of American soldiers. A fall from his horse proved fatal to Louis Cook and he died near Buffalo in October of 1814.

In 1786, When Father Femin moved the mission to Kahnawake near the Lachine Rapids, and as previously mentioned, he arranged with the Sulpicians who owned the Island of Montreal to take some of his Indians into their Mountain Mission. The site is marked today by the two old stone towers, built in 1694. They still stand on the north side of Sherbrooke Street at Atwater, in the grounds of the Grand Seminary. Marguerite Bourgeoys taught the Indian children in the western tower. Twenty years later liquor had again become a problem and the Indians were moved to the north side of the mountain and relocated at the mission of Sault-au-Recollet. In 1704, some of the Algonquins went to the Baie d’Urfe area on Lake St. Louis and a number of Nipissings moved to Ile-aux-Tourtes at the foot of the Lake of Two Mountains. In 1721, the Sulpicians moved all of them to their Seigneury of Two Mountains at Oka, some forty miles northwest of Montreal and on the Ottawa River.

The Seigneury of Two Mountains was granted to the Montreal Seminary of St. Sulpice in 1718, for the maintenance and instruction of the Iroquois and a number of Algonquians and Nipissings. In 1733, the order petitioned for and received an additional grant of land. At Oka, the Mohawks carried on with their agricultural way of life or found summer employment as pilots and raftsmen on the Ottawa and St. Lawrence Rivers. Often they worked side by side with other Mohawks from Caughnawaga and St. Regis. The Algonquins preferred a migratory lifestyle of hunting, fishing and trapping, away from the Seigneury the greater part of the year.

It is interesting to note and in light of recent events, that the Seigniorial grant was not to the Sulpicians as such, but in their capacity as missionaries, to the Indians who were recognized as a distinct nationality. They were considered as valuable allies of the French and indispensable in the fur trade. Also, following the British conquest, the Sulpicians were allowed to keep their property but no legal titles were granted. The occupants were only left in possession. Matters remained in that state until 1841 when the Seminary was able to obtain confirmation of its title at Oka and without any modification, whether with reference to the Indians or to the support of education or of the poor.

Within a few years, the Seminary endeavoured to be rid of any obligation to the Indians and to become absolute owner of the Seigneury of Two Mountains. They urged the government of the day to set aside sixteen hundred acres of land to the north of Montreal Island for the relocation of the Oka Indians. Thus the Sulpicians would remain absolute owners of the lands which were originally granted rather more for looking after the Indians than for their own use. The Indians refused to move and a long series of conflicts began and unfortunately lasting to the present day. This was a direct breach of trust on the part of the Sulpicians. It is quite evident that the priests like so many others before and after them, took advantage of their clerical robes and pursued an ongoing concern for the financial prosperity of the order.

The Indians lost a great deal of confidence in the sincerity of their spiritual guides. By 1868, many of them had decided to abandon the Catholic faith. The Methodists had gained a foothold among them. A small church was erected on a site that had been an Indian possession for over sixty years and had a registered deed. The Sulpicians reacted with persistent harassment and a curtailment of privileges which the Indians had enjoyed since the beginning of the relationship. The conflict ended with the burning of both the little church of the Protestants and the large stone church of the Sulpicians. This outrage against all the better feelings of humanity was only the culminating act in a long series of hardships inflicted on the Indians at Oka.

When the American Revolutionary War began in 1775, the six nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, with the exception of the Oneidas, sided with the Tories and were enlisted as military auxiliaries. This was particularly true of the Mohawks, who had enjoyed a special friendship with Sir William Johnson and the men around him. It was an entirely different situation with the ‘Christian’ Indians of Quebec, so long under the protection and spiritual guidance of the Catholic Church. By the time that Guy Johnson and Joseph Brant reached Montreal in the summer of 1775, Governor Guy Carleton had already approached the Mohawks at Caughnawaga and St. Regis to provide a few warriors for provincial service. He was very clear on the matter that they would not bear arms as an offensive force but would act as scouts. In that capacity they saved the lives of many British soldiers. Carleton and Handyman pretty well stayed with this decision through the war.

A military presence was established at Caughnawaga, St. Regis, Oka and in the Abenaki village at St. Francis. All during the war, Indians from these villages served with scouting and spying parties, along the Richelieu valley and as far as the Hudson and Mohawk valleys. Some accompanied Sir John Johnson on raiding forays into these areas. A large number of some five hundred were with Burgoyne in the campaign of 1777. There was never unanimous support for the British cause. Many Indians remained neutral; even sided with the French Canadians in their feelings against the Tories.

There has always been a question of just what lands the “Christian” Indians owned or had legal title to. It is still a very important and a disturbing question of the day, as we have seen at Oka. The Jesuits were granted the Seigneuries of Laprairie and Sault St. Louis. Following the British conquest and the decision to end the Jesuit missions, the Seigneury of Sault St. Louis was vested in the government and given to the Mohawks. Over the years, the Indians have disposed much of this land and the only part that remains is the reservation now occupied by the Mohawks at Kahnawake. The St. Regis Indians had vested interests and a reservation in their area and even had land grants in what became the Township of Dundee. The early settlers paid rents on their lots on this land until a purchase agreement was arranged by Quebec. Over the years and existing to this day, the Caughnawaga and St. Regis Indians have had to take legal actions, either to reclaim, land that they feel has been taken from them, or to prevent further erosion of land rights or concerning differences in interpreting old agreements. Modern highways and the St. Lawrence Seaway have taken up hundreds of acres of arable and residential land on these reservations. They do have the satisfaction that their boundary lines are finite.

This is not the case at Oka where the Indians have always had property problems. There the Sulpicians never granted them any part of the Seigneury. The fact is that following the end of the Seigniorial system in Quebec in 1854, the Sulpicians sold off most of the land for the valuable timber. This reduced the hunting limits of the Indian families and they had to rely more and more on their small plots of land. Over the years they had moved away from the old village and acquired more farm land. Today they live side by side with French and English farmers. They have never had a reservation or a defined area like Caughnawaga or St. Regis. If they do not have deeds they most certainly have ancestral and acquired rights. Up until nearly a hundred years ago, a large part of the area was sand plain. Many of the French and English families who summered there along the Ottawa River, arranged the planting of the pine plantations that are now forests and in which are located the golf course as well as many Indian homes and playgrounds. The Indians have always claimed this ‘common’ ground by acquired right. Their native burying ground is located there. A

Although many Indian families at Oka can trace their ancestry there for over two hundred and fifty years, their problems have still not been resolved. Many others have now been created that unfortunately will last for years to come. There are divided opinions throughout Canada and the healing process will not be easy. Perhaps this brief history of the Mohawk or ‘Christian’ Indians in Quebec will serve to place them in a proper time frame and historical context.

Source Notes:

Historic Caughnawaga, E. J. Devine, S.J.

Historic-St. Francois-du-lac, Thomas M. Charland

The French Occupation of the Champlain Valley, Guy Omeron Coolidee

The Loyalists of Quebec, Heritage Branch U.E.L.A.C.

Indians of the Lake of Two Mountains, Protestant Defence Alliance of Canada.

i) The Mohawks were not settled by the Government

of New France in Kahnawake, Akwesasne and Kanesatake. Our ancestors moved

to these lands to stake a claim to the northern part of our territory

call Kanienkeh, meaning land of the flint. They also wanted to take advantage

of economic opportunties to engage in trade between Montreal and Albany,

the forerunners of free trade. We call ourselves Kanienkehaka, meaning

People of the Flint. The Catholic religious orders, the Jesuits and Sulpicians

moved to our communities to tend to the religious needs of our people

who developed a syncretic religion of Catholicism and traditional beliefs

ii) Father Fremin did not arrange to move some Mohawks, Hurons and Algonquins

to the Mission of the Mountain. These people wanted to go of their own

free will and resettled the island of Montreal that we call Tiohtiake.

They only asked the French "permission" as a courtesy that they

would give them protection from French settlers and brandy traders.

iii) Our ancestors relocated our villages of Kahnawake due to the horticultural

land use cycle of our ancestors and not the Jesuits. The Mission of the

Mountain was moved to Sault-au-Recollet due to the French desire for the

best real estate now in downtown Montreal. And the Sulpicians eyed a substantial

profit from the move. The Sulpicians and Jesuits always claimed the moves

were in the best interests of the Mohawks when they were in their best

interests financially $$$!

iv) The Pines in Kanesatake were planted by the ancestors of both the

Mohawks and English and French settlers and families that lived in Oka

region over one hundred years ago.