When British General John Burgoyne began marching south with his army in 1777, the Loyalist families in upper New York and Vermont, felt that the uprising of the rebels would be over soon and joined in the fighting to keep their part of the world loyal to the King. Left behind to manage the farms and families alone, when their husbands left to fight, the Loyalist women served as providers and caregivers, sometimes for very large families. But they were to play another role as well, which became very important to the Loyalists. They became shelters for escaped prisoners, drop-off points for the Loyalist agents passing through and food-providers for those heading north. They were aware that if they were caught, they would either go to jail or worse. The Vermont Council of Safety recounted the various ways in which the Loyalist women aided the enemy: by providing intelligence or by feeding, housing or supplying the Loyalist or British soldiers. The Council resolved that these families be removed to within Patriot lines.

Most of the colonies adopted similar laws, but the Loyalist wives were not forced to leave immediately, so that they continued serving a very useful purpose, helping the British cause by allowing messages to get through between the Loyal Block House on Lake Champlain and General Clinton in New York City. The families stayed on their farms until the farms were confiscated. The women and children were given twenty days to leave the area or be imprisoned.

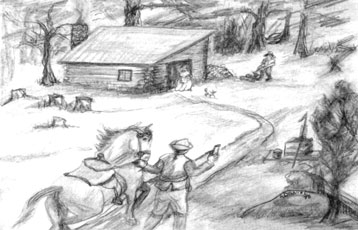

One such case was the family of Henry Ruiter, which was living near Hoosick, in upper New York State. Their sons were nearing the age of twelve and fourteen and would soon be forced to join the State Militia. Henry Ruiter wrote to Major Mathews at Quebec in May 1780, asking him to bring the boys into Canada with the next raiding party and also stated that his wife Rebecca was greatly oppressed. Rebecca had been threatened at gun-point if she would not tell the rebels where her husband was hiding. The boys must have been rescued, because when Rebecca Ruiter was forced to leave in September 1780, she had two girls with her. Other women who accompanied Rebecca at that time were: Sarah Cameron, wife of Duncan Cameron; Catherina Best, wife of Jacob Best, Sr.; Elizabeth Best Ruiter, wife of John Ruiter; Elizabeth Tretcher; Arcante Weis; Maria Young; and Susannah Lampman. And from Vermont the following women were forced to depart within twenty days, providing the necessary supplies for the trip themselves: Elizabeth Hogle, wife of John Hogle, who had been killed at the Battle of Bennington; Jane Hogle, wife of Francis Hogle, along with three children of Simeon Covell; and Elizabeth Bowen, who left with five other women, thirty-one children and only one pair of shoes in all. Rebecca Ruiter died in Chambly in 1781, probably as a result of the terrible conditions under which she had been living for several years.

There had to be secrecy within the neighbourhood. People were divided in their loyalties and it was difficult to know whom to trust. Sometimes the husbands would come home during the night, but not often, and only if they were delivering messages to other agents. The whole family was sworn to secrecy, because one word by a child to another playmate could cause the family to be sent away or jailed.

When the blow came and they were ordered to leave, it was a sad day for everyone, but they took what they could carry and paid to get to Crown Point, on Lake Champlain. From here they were transported by ships, which the British provided, to carry them to Pointe de Fer and then on to St. Johns (now Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu).

Again there was more disappointment! Their husbands were in Loyalist units in the various posts. Barracks had been built in refugee centres to house the many families coming into Quebec. As early as 1779, the following Provision Lists give the numbers: Montreal: 202; Pointe Claire and Lachine: 126; Machiche: 190; Sorel: 87; St. Johns: 209. The numbers increased as the years progressed and by 1783, when it was learned that there would be no provisions in the Treaty of Paris to assist the loyal Americans, the Government took a stand and decided to settle the families west of the Ottawa River and along the St. Lawrence, which became Upper Canada and then Ontario.

After the Constitutional Act of 1791, the land in Lower Canada, for which the Loyalists had been petitioning for several years, was surveyed into townships, and granted to those who had stayed in the area. Henry Ruiter was granted part of the Township of Potton. He married again and had a large family here, where he built mills and roads. Many had accepted the grants in the western part of Quebec (Upper Canada after 1791) and had left to go there in 1784. But the Loyalist women felt that they had waited long enough and wished to get started on the final chapter of their last adventure. These courageous women were the pioneers of the Eastern Townships ... together with the Loyalist men.

By Jean Darrah McCaw, U.E., C.M.H.

Branch Genealogist, Sir John Johnson Centennial Branch

The United Empire Loyalists’ Association of Canada

REFERENCES:

1. Janice Potter-MacKinnon, While the Women

Only Wept, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993.

2. Walter S. White, Pages from the History of Sorel 1642-1958, Berthierville,

Quebec, 1958.

3. Provision Lists. Public Archives of Canada, Haldimand Papers, Microfilm

Roll MG 21 V.B 166.

4. Sir John Johnson Centennial Branch, UELAC, Loyalists of the Eastern

Townships. of Quebec, 1984.