December 2, 2017

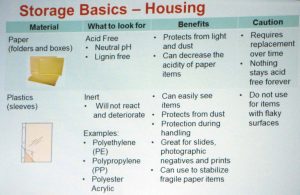

Archives of Ontario Conservator Adriane VanSeggelen spoke on “Accessing and Preserving Family Heirlooms”. Adriane’s specialty is preservation of paper of all types. She told us what to do if we’re still storing old family photos in shoeboxes in the basement or old grocery store cartons in the garage, and how to remedy these situations which could lead to the irreversible degeneration of photographs and paper documents.

Archives of Ontario Conservator Adriane VanSeggelen spoke on “Accessing and Preserving Family Heirlooms”. Adriane’s specialty is preservation of paper of all types. She told us what to do if we’re still storing old family photos in shoeboxes in the basement or old grocery store cartons in the garage, and how to remedy these situations which could lead to the irreversible degeneration of photographs and paper documents.

The ideal storage condition for any type of paper (documents or photos) is between 18 and 20 degrees Celsius, with 50% humidity. As we move our family treasures to better storage, we should examine each item first, to make sure it is not already suffering from insect infestation or mould. Old books, for example, may have a red powder on their binding and cover; that is red rot and the book should be wrapped in acid-free tissue paper to keep the rot from other materials.

Adriane talked about appropriate ways to handle items without causing further damage. Photographs, negatives, slides and anything metal should always be handled wearing gloves, and only picked up by the edges. Gloves can be cotton (washable and re-usable) or nitrile or vinyl. Books and documents can also be handled with gloves but sometimes this makes turning pages difficult and can actually damage fragile corners. It is quite acceptable to handle paper with bare hands, as long as your hands are freshly washed and dried. Adriane said she even has to remind herself that, every time she touches her hand to her hair or face, she needs to wash her hands again before touching any papers: the oils on our skin are very harmful to paper.

Adriane provided useful tips for dealing with photos presently housed in “magnetic” albums, PVC sleeves or glassine envelopes. Such items should IMMEDIATELY be rescued. (Glassine envelopes are okay for negatives, as there is no gel to stick to the envelope.) To remove photos from the “magnetic” albums, Adriane told us to use dental floss; gently and slowly slide a length of it underneath the photo, working it under with a hand at each end of the floss to loosen the photo from the sticky page. If this does not work, then scan and digitize the photo before it deteriorates further: glue from the sticky page below and the plastic cover above are both working to degrade the photo.

Adriane provided names of companies that supply archival-quality storage items but pointed out that many can be obtained locally as well. Acid-free plastic sleeves can be purchased at Staples, Costco and elsewhere. Michaels sell acid-free boxes designed specifically for storing photographs. Many places sell soft (2B) pencils which are recommended for labelling photos on their back, along an edge, as long as you don’t press hard. And she pointed out that printer paper is all acid-free, so it can safely be used as divider sheets between other documents, or you can fold a sheet of printer paper in half to enclose documents and provide a way to lift a fragile document. She also discussed “sandwiching” a fragile piece of paper with a printer page under and over it if you need to flip the fragile one; always support it with your full hand, fingers outspread.

Adriane provided names of companies that supply archival-quality storage items but pointed out that many can be obtained locally as well. Acid-free plastic sleeves can be purchased at Staples, Costco and elsewhere. Michaels sell acid-free boxes designed specifically for storing photographs. Many places sell soft (2B) pencils which are recommended for labelling photos on their back, along an edge, as long as you don’t press hard. And she pointed out that printer paper is all acid-free, so it can safely be used as divider sheets between other documents, or you can fold a sheet of printer paper in half to enclose documents and provide a way to lift a fragile document. She also discussed “sandwiching” a fragile piece of paper with a printer page under and over it if you need to flip the fragile one; always support it with your full hand, fingers outspread.

With such good information, we can now preserve most of our family documents for posterity. Of course, scanning and digitizing everything is also a wonderful goal, as long as the digital files are stored on hard drives (not CD-ROMs) and preferably mirrored on a “cloud” site as well. But just in case we don’t all get that done immediately, Adriane’s tips will mean that we can more easily preserve our past.

September 23, 2017

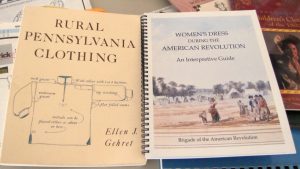

Our topic was “Loyalist Clothing: Design and Fabric for Period-Appropriate Attire”. We first screened a video of “Getting Dressed in the 18th Century” produced by the National Museums of Liverpool (England). Having watched an upper-class woman being dressed by her two maids, Nancy Cutway then spoke about her linsey-woolsey dress and accessories and proceeded to undress, layer by layer, so the audience could examine her cap, mantua, petticoats, pockets and chemise. Nancy pointed out that her attire was more “everyday” or working-class … probably. The problem is that most 18th century designs we know about come from the clothing of the wealthy, in museums, and very little has survived of the clothing worn by the average person.

Our topic was “Loyalist Clothing: Design and Fabric for Period-Appropriate Attire”. We first screened a video of “Getting Dressed in the 18th Century” produced by the National Museums of Liverpool (England). Having watched an upper-class woman being dressed by her two maids, Nancy Cutway then spoke about her linsey-woolsey dress and accessories and proceeded to undress, layer by layer, so the audience could examine her cap, mantua, petticoats, pockets and chemise. Nancy pointed out that her attire was more “everyday” or working-class … probably. The problem is that most 18th century designs we know about come from the clothing of the wealthy, in museums, and very little has survived of the clothing worn by the average person.

Anne Redish then offered powerpoint slides showing attire from several time periods within the 18th century and involving people of varying social status. She displayed several garments, both her own and some on loan from the Dominion Costume Branch, pointing out what was accurate about them and what was not. She recommended a number of reference books on the subject and provided some excellent handouts for our further consideration and “homework”.

Due to the extreme heat of the day, we decided as a group to postpone consideration of fabrics appropriate to the 18th century to a later time. We did learn that wool and linen are the most appropriate choices, colours should be relatively subdued — no neon orange! — and stripes or dotted patterns with a definite vertical look are fairly accurate while large recurring or reversing prints are not.

We hope in the future to see several more members honouring their Loyalist ancestors by dressing in clothing they might have worn.

May 30, 2017

We met at Minos Village Restaurant for our Banquet/Luncheon — we can’t decide what to call it! (Some say a banquet is only at night.)

There was a lot to look at before sitting down.

We had collected about 26 door prizes from several generous donors, including a season’s pass kindly donated by the Lennox and Addington County Museum and Archives. Winners could pick their prize from those that remained when their number was drawn, so folks looked them over carefully before lunch.

We had collected about 26 door prizes from several generous donors, including a season’s pass kindly donated by the Lennox and Addington County Museum and Archives. Winners could pick their prize from those that remained when their number was drawn, so folks looked them over carefully before lunch.

Lynn Bell has been busy carving and painting over the winter. He showed two display boards he had made, Notable Kings and Queens of England, and British Professions and Occupations.16th to 19th Centuries. We were all very impressed with the worksmanship and detail that went into them. Lynn didn’t tell us which kings are his direct ancestors!

Lynn Bell has been busy carving and painting over the winter. He showed two display boards he had made, Notable Kings and Queens of England, and British Professions and Occupations.16th to 19th Centuries. We were all very impressed with the worksmanship and detail that went into them. Lynn didn’t tell us which kings are his direct ancestors!

As usual, the colours (Canadian, Ontario and Loyalist flags) were paraded in and set at the front. Thanks to Jim Long, David Lawrence Smith and Peter Johnson who carried them in, and to Terry Hicks who plays the anthems at the beginning and end of our gatherings. Past President Dean Taylor emceed the proceedings as the president was out of the country.

As usual, the colours (Canadian, Ontario and Loyalist flags) were paraded in and set at the front. Thanks to Jim Long, David Lawrence Smith and Peter Johnson who carried them in, and to Terry Hicks who plays the anthems at the beginning and end of our gatherings. Past President Dean Taylor emceed the proceedings as the president was out of the country.

After a delicious lunch, our speaker was David More, a PhD candidate in history at Queen’s University. He spoke about “How Thousands of Loyalists Were Shipped to Eastern Ontario and how such maritime industry shaped the development of Central Canada.” We learned that long before the Loyalists began to arrive in what would become Canada, the inhabitants of New France invented a new type of boat — a bateau — to haul cannons and supplies up the St. Lawrence River from Montreal, in order to transit the rapids and supply the western forts during the American Revolution and even earlier during the Seven Years War.

After a delicious lunch, our speaker was David More, a PhD candidate in history at Queen’s University. He spoke about “How Thousands of Loyalists Were Shipped to Eastern Ontario and how such maritime industry shaped the development of Central Canada.” We learned that long before the Loyalists began to arrive in what would become Canada, the inhabitants of New France invented a new type of boat — a bateau — to haul cannons and supplies up the St. Lawrence River from Montreal, in order to transit the rapids and supply the western forts during the American Revolution and even earlier during the Seven Years War.

The bateau was pointed at both ends, like aboriginal canoes, but was much more sturdy than the delicate canoes made of birchbark. The much larger and squared-end Durham boat could not be hauled up the rapids. The bateau was ideal. It was usually steered by one helmsman while four other men rowed. It could transport about four to five tons of cargo, and could be hauled up the 12 rapids that came between Montreal and Prescott.

Mr. More made us aware of just how many tons of food and gun powder, as well as the guns, had to be transshipped from ocean-going vessels to these bateaux. Then, of course, after the war ended, thousands of Loyalists needed to be transported upriver into the heart of Upper Canada, together with their supplies and their animals, There was a fleet of 600 bateaux in service during the Revolution, employing between 3,000 and 6,000 men, almost all French-speaking. Many were also employed at Carleton Island, off Kingston, once the British Navy set up a shipyard in 1780 and began building warships such as HMS Ontario, launched in 1780, and HMS Haldimand.

An interesting fact was that the government maintained a fleet of 50 bateaux after the Revolution to serve the area of Montreal to Kingston. No civilian-owned boats were permitted on Lake Ontario until after 1787.

Few of us had ever given much thought to exactly how our Loyalist ancestors reached this area, or perhaps we thought they rowed boats upriver themselves. Now we’ll have a better grasp of the situation when we next see a re-enactment of Loyalists being rowed ashore in a bateau.

March 25, 2017

left to right: Paul Woodrow, Reg Wales Jr. UE, Reg Wales Sr. UE, President Peter Milliken UE.

Mr. Woodrow is Reg. Jr’s father-in-law who assisted the Waleses with preparing their claims.

After a lunch of scrumptious soup provided by the Hospitality Committee, and sandwiches and goodies contributed by members, about 55 people were present for the meeting itself.

UEL Certificates were presented to Reginald Laverne Wales (Sr.) and his son Reginald James Glenn Wales (Jr.) after proving their descent from David Babcock UE. David Babcock settled in Kingston Township. He was a Captain of the Embodied Refugees who fought at the Battle of the Block House in Bergen Wood, New Jersey in 1780.

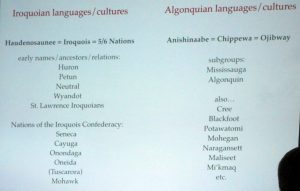

Dr. Laura Murray, Professor of English and Cultural Studies at Queen’s University, spoke on “How the Deal Went Down: Indigenous People and the Establishment of Kingston, 1783.”

Dr. Laura Murray, Professor of English and Cultural Studies at Queen’s University, spoke on “How the Deal Went Down: Indigenous People and the Establishment of Kingston, 1783.”

Dr. Murray explained that the First Nation group primarily occupying the Kingston area at the end of the American Revolution were Algonquians, specifically the Mississauga. Those with whom the Loyalists had collaborated during the Revolution, who had fought alongside the British forces, were primarily Iroquois, who lived in New York province. The two groups had quite different language and culture, and should not be thought of as unified.

Laura mentioned that it is often said that Cataraqui means “place where there is clay” or “where the limestone is”. However, her studies lead her to believe that Katarokwi derives from the Huron language and means “Swampy Place”. This certainly fits the area around the Inner Harbour where Indigenous trading encampments were just outside the perimeter of the original Fort Frontenac.

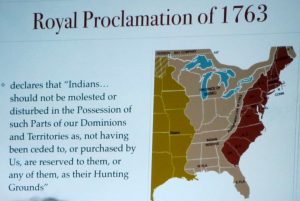

Laura discussed the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which reinforced the rights of First Nations to their historic hunting lands. The red area on the map represents the western edge of the 13 Colonies. Colonists could not claim lands individually west of that line into the beige-coloured area, but there was great pressure on the government to let the colonies expand westward. This Proclamation became one reason why many Iroquois sided with the British against the Americans during the Revolution, believing that the British would preserve their hunting grounds.

Laura went on to show some interesting letters exchanged between Governor Haldimand and people such as the surveyors Samuel Holland and John Collins, Major Ross, and Sir John Johnson. In the summer and fall of 1783, John Collins began to survey the area around Cataraqui. In October, Captain William Crawford presided over the “Crawford Purchase” from the Mississaugas of “all the Lands from Toniata or Ouagara River [Jones Creek near present-day Mallorytown] to a River in the Bay of Quentie [near Belleville] within Eight Leagues of the Bottom of said Bay including all the Islands, extending from the Lake Back as far as a man can Travil in a day.” This distance came to be interpreted as 2 or 3 townships in depth, as far as Tamworth on the west and Westport on the east.

Sir John Johnson offered to create a “deed of Cession” but no deed has survived or been found so it is not certain if this was done. Nowhere in the letter documenting the Crawford Purchase is it indicated that the Mississauga swore allegiance to the King or intended to give away their lands.

Then, in June 1784, the Loyalists began to arrive.

It was an informative and thought-provoking talk.

January 28, 2017

We started with a hot potluck lunch provided by the Hospitality committee and members. Lots of good food, and the leftovers went to St. George’s Church for their Lunch By George program the following Monday. It must be ingrained into the DNA of Loyalists never to let food go to waste!

We then heard from Deb McAuslan about “Palatines: Refugees from a Different Time”. Her excellent presentation conveyed to the large audience just how desperate the Palatines were when they decided to leave Germany for England. Bad crops that killed the vineyards (which would therefore not have produced fruit again for seven years), incursions into the area by French armies, and British propaganda extolling the wonders of land in America all contributed to a flood of emigrants through Rotterdam to England.

We then heard from Deb McAuslan about “Palatines: Refugees from a Different Time”. Her excellent presentation conveyed to the large audience just how desperate the Palatines were when they decided to leave Germany for England. Bad crops that killed the vineyards (which would therefore not have produced fruit again for seven years), incursions into the area by French armies, and British propaganda extolling the wonders of land in America all contributed to a flood of emigrants through Rotterdam to England.

At first the English government welcomed them … until they began to realize just how many thousands were coming down the Rhine and crossing the Channel. The refugees were accommodated in old warehouses and given meagre rations of food, but the locals in London began complaining that these Germans were getting food and jobs that should have gone to native-born Britons.

The solution arrived at was twofold: since the Palatines were generally Protestant, they could be sent to Ireland to help “dilute” the Roman Catholic population there. Many became workers for large English landowners, primarily in County Limerick. Thousands more were put on ships bound for New York colony, with the intent that they would be located on less-productive lands that were not good for farming, but contained thousands of pine trees that the Palatines could turn into pitch and tar for the British Navy. The project failed, because Governor Hunter of New York knew nothing about making pitch, and the financial support from England ran out before any could be produced.

It was a most interesting and informative outline of events that happened to the parents of many from the Loyalist generation.

The meeting was also the occasion of presentation of a Loyalist Certificate to Christopher Roney, who has proven his descent from UE Loyalist John William Clement, a settler in Ernestown.

photo from left: Peter Milliken, Branch President; Anne Redish, Branch Genealogist; Christopher Roney; Gerry Roney, Chris’s father and Branch Treasurer. photo by Nancy Cutway

Looks like some intense discussions were taking place as people finished their lunch and lingered over coffee. Loyalists always find a lot of interesting things to talk about.